- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- ,

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 0

- 0

- ,

- 0

- 0

- 0

HIV diagnosis rates in African-born immigrants in the U.S. are 6 times higher than in the U.S.-born population. African-born immigrants in the U.S. are typically diagnosed at later stages of HIV infection than U.S.-born residents. Interestingly, African-born immigrants with HIV have lower mortality after diagnosis. African-born immigrants account for higher rates of HIV among women, higher rates of heterosexual transmission and lower rates of injection drug use. Despite the distinct epidemiological profile of African-born immigrants in the U.S., surveillance reports often group African-born residents with U.S.-born African-Americans.

African-Americans bear the heaviest burden of the HIV epidemic in the U.S. Although African-Americans represent 12% of the total U.S. population, they accounted for 45% of the new HIV infections in 2015. The proportion of African-born immigrants within this group has not been measured. Most new HIV infections in the U.S. occur among men who have sex with men followed by African- American heterosexual women.

-MIGRANT POPULATIONS

MIGRANT POPULATIONS

AND HIV

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- .

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- M

- i

- l

- l

- i

- o

- n

- U

- n

- k

- n

- o

- w

- n

- U

- n

- k

- n

- o

- w

- n

- U

- n

- k

- n

- o

- w

- n

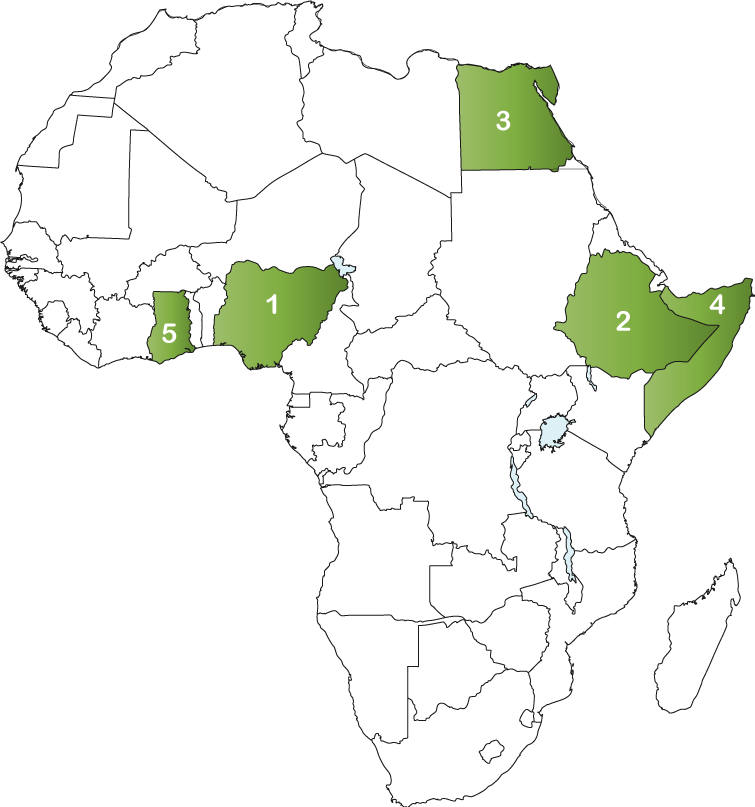

TOP 5 AFRICAN COUNTRIES

OF ORIGIN FOR MIGRANTS IN UNITED STATES

- 1. Nigeria: 237,221

- 2. Ethiopia: 184,022

- 3. Egypt: 159,562

- 4. Somalia: 145,579

- 5. Ghana: 134,338

-TOTAL POPULATION

PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV

- 0

- 1

- ,

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 0

- 1

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- ,

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 0

- 0

NEW INFECTIONS

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- ,

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 0

- 1

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

HIV TREATMENT CASCADE

KEY AND AFFECTED POPULATIONS

44% of new infections among heterosexuals

26% of new diagnoses

67% of new infections

African-American gay and bisexual men account for more HIV diagnoses than any other group in the U.S. In addition to risk factors affecting all gay and bisexual men such as a larger percentage of men with HIV in sexual networks, several factors are more specific to African American gay and bisexual men. These include socioeconomic factors, smaller and more exclusive sexual networks and lack of awareness of HIV status. In addition, stigma, homophobia and discrimination are barriers to accessing and receiving healthcare services including HIV testing, treatment and prevention services.

Sex workers may be at an increased risk of contracting HIV because they may engage in sex without condoms with multiple partners. Few population-based studies have been done on HIV among sex workers and none among African migrant sex workers. One of the main HIV prevention challenges is the lack of data on sex workers in the U.S. The number of migrants who are sex workers is unknown, though the total number of sex workers is estimated to be 1 to 2 million people in the U.S. Given the diversity among this group, targeted prevention efforts are necessary to reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

8% of new diagnoses

The transmission of HIV among Injection drug users is three times lower among foreign-born Black people than among US-born residents. In 2015, 6% of HIV diagnosis were attributed to injection drug use. 59% of HIV diagnosis attributed to injection drug use were among men and 41% among women. Of the HIV diagnosis attributed to injection drug use, 38% were among African-Americans. Some of the prevention challenges among injection drug users include the sharing of needles, syringes and other injection equipment. Injection drug use can also reduce inhibitions and increase behaviours such as having sex without condoms, with multiple partners and trading sex for money or drugs.

HEALTH

The United States’ migration story is a complex and difficult one. The first migrants from Africa to the United States (U.S.) were forced to migrate as part of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Between 1525 and 1866 a total of 12.5 million Africans were shipped to the Americas of which 10.7 million survived and disembarked in North America, the Caribbean and South America.

Voluntary migration from Africa to the U.S. did not begin until the 1980s. From 1980 to 2013, the sub-Saharan African immigrant population in the U.S. increased from 130,000 to 1.5 million. As of 2013, there were 1.8 million Africans of which 82% were from sub-Saharan African in 2013.

In 2014, there were a total of 11.1 million unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. a number that has remained unchanged since 2009. Though Mexicans make up a little over half of the population of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S., the number of unauthorized immigrants from countries outside of Mexico has grown from 325,000 since 2009, to an estimated 5.3 million in 2014. Migrants from Asia and Central America constitute a large part of the increase, however the number of sub-Saharan African migrants has also continued to grow. Additionally, the number of unauthorized adult migrants who have lived in the U.S. for at least a decade has grown from 41% in 2005 to 66% of adults in 2014.

The U.S. is considered one of the most desirable countries in the world to migrate to given its large economy. Immigrating to the U.S. is difficult and complex to navigate. From 1993 to 2010, the U.S. immigration policy response to HIV focused on preventing HIV-positive people from entering the country. Unless a waiver was granted, HIV-positive status was regarded as grounds for inadmissibility to the U.S. for applicants for short-term non-immigrant visas and for lawful permanent residence. While the removal of the ban on barring entry to HIV positive migrants to the U.S. was lauded as a victory, the removal of mandatory HIV testing is seen as a missed opportunity for HIV counselling and testing by some.

Though studies suggest that immigrants to the U.S. are generally healthier than the native-born population, the “healthy migrant” effect wears off soon after arrival. The African-born population in the U.S. is generally concentrated in large urban centres. Although African-born immigrants in the U.S. have typically had higher rates of English proficiency, advanced degrees and higher rates of employment than foreign-born U.S. residents overall, they also experience higher rates of poverty. In recent years, unemployment among African-born immigrants in the U.S. has risen.

Policies that limit healthcare access to immigrants have become prevalent in recent years given the increase in migration. In the U.S. access to healthcare is limited to those who have health insurance, and those who can pay out of pocket for their healthcare services and treatment.

The U.S. does provide some healthcare coverage to eligible populations via Medicare, the federal health insurance program for people who are 65 or older, certain younger people with disabilities, and people with End-Stage Renal Disease (permanent kidney failure requiring dialysis or a transplant). Medicaid is a social healthcare program that provides free or low-cost medical services to eligible low-income adults, children, pregnant women, seniors, and people with disabilities. Both Medicare and Medicaid are only avaiiable to citizens and permanent residents of the U.S. Unauthorized immigrants and temporary visa holders (those with student or temporary work visas) are not eligible for Medicaid, except for Medicaid coverage of emergency room services.

A range of social, economic, and demographic factors affect migrants’ risk for HIV, such as stigma, discrimination, income, education, and geographic region. This problem is further compounded by lack of access to healthcare for many migrants in the U.S. Immigrants in the U.S. have extremely low rates of health insurance coverage and poor access to healthcare services. Almost half of all immigrants in the U.S. are uninsured. Uninsured immigrants face serious barriers to accessing medial care and have to pay more out-of-pocket for the healthcare services they do receive. This can drive many into debt or financial insolvency.

Immigrants and undocumented migrants in the U.S. often have to rely on a patchwork system of safety-net clinics and hospitals for free or reduced-price medical care, including state- and county-owned facilities, as well as charitable and religiously affiliated facilities. However, those who are unable to navigate this complex patchwork system are often left with no healthcare access.

Black men who have sex with men have experienced a number of challenges to accessing HIV services in the U.S. such as lack of access to culturally competent services, stigma and discrimination, inadequate HIV services in correctional institutions, and insufficient service availability in areas where these populations reside.

Black men who have sex with men also face structural barriers that increase HIV risk. These include unemployment, less education, lower income, and run-ins with the criminal justice system, compared to their white men who have sex with men counterparts. HIV care outcomes were also lower for Black men who have sex with men in the U.S. compared to men who have sex with men from other groups). Research suggests that while African-Americans may be confronted with challenges such as institutionalized racism and poverty, Black immigrants may face these challenges in addition to others such as language barriers.

Black men who have sex with men and Black women are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic in the U.S. Though there is a misperception that Black men who have sex with men and Black women engage in “riskier” behaviour than others, several studies have shown that these two groups have similar numbers of sexual partners and use condoms as often as their white counterparts. Though behaviroual risk factors are important, they do not fully explain the racial disparity of the HIV epidemic in the U.S. African American and African-born immigrants face serious challenges accessing housing, education, employment, and healthcare. The high rates of HIV among Black communities are not the result of risky behaviour, but instead, structural inequalities that render this population more vulnerable to HIV infection.

POLICY

The burden of the HIV epidemic affects the Black population the most severely in the United States (U.S.). Although African-Americans represented 12% of the US population in 2015, they accounted for 45% (17,670) of HIV diagnoses. One of the main issues driving health inequities in the U.S. is the lack of affordable care and policies that limit access to healthcare for immigrants. The high costs of healthcare and the erosion of health insurance coverage given the recent change in government in the U.S. has left many without access. Immigrants in the U.S. have extremely low rates of health insurance and poor access to healthcare services. Eligibility criteria for healthcare coverage in the U.S. is very narrow and as a result many documented and undocumented migrants are unable to access healthcare services.

Policies should be designed to improve service delivery to reinforce migrant-friendly public-health services and establish minimum healthcare standards for all vulnerable migrant groups. Increasing HIV testing and linkage to care for key populations such as African-American men who have sex with men and Black heterosexual women (two groups disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic in the U.S.) can help to reduce the transmission of HIV. Providing antiretroviral therapy early on to people with HIV has been shown to reduce the risk of transmitting the virus to others by 96%.

Implementing policies to increase prevention efforts, providing culturally appropriate care and increasing harm reduction efforts have been shown to be effective in reducing the risk of transmitting HIV, thereby reducing inequities in the epidemic. There are a number of cost-effective approaches to reducing the risk of HIV infections. These approaches are especially effective when they are tailored to address the social, community, financial, and structural factors that place specific groups at risk. However, this remains difficult to do in the U.S. given that surveillance efforts among Black populations do not differentiate between American-born African-Americans and African-born immigrants.

In general, migrants are more vulnerable to HIV because of isolation, insecure jobs and living situations, fear of accessing government services and lack of access to sexual and reproductive healthcare and undocumented migrants have the additional barrier of lack of legal protection.

In the U.S. migrants face particularly difficult challenges in accessing healthcare. Given that healthcare services and treatment are very expensive and government run health insurance only affords coverage with very specific eligibility criteria, immigrants are more than three times as likely to be uninsured (44 percent) compared to U.S.-born citizens (13 percent).

Many Americans receive health insurance coverage through their employer. However, despite the high rates of employment among immigrants in the U.S., fewer immigrants have employer-sponsored health insurance. Lack of healthcare is further complicated by the fact that unresolved health problems can limit immigrants’ ability to maintain productive employment, particularly given that many work in physically strenuous jobs or in jobs in which there is a high incidence of occupational injuries. Labour policies that do not protect workers and instead favour employers has resulted in many employed immigrants not having access to employer sponsored health insurance. The health, labour and immigration sphere must be more integrated to provide equitable access to authorized migrants in the U.S. Given that the unauthorized migrant population in the U.S. is 11 million people strong, extending healthcare access to this group will keep this population healthier and further reduce healthcare costs in the future.

THE RESPONSE

In the United States (U.S.), African-born immigrants are often grouped with U.S.-born African-Americans for surveillance purposes. These two groups are not homogenous and require tailored approaches to prevention and treatment as both groups have different cultural contexts and health beliefs, attitudes, practices and behaviours.

The increasing immigration of African-born people to the U.S. along with incomplete surveillance data highlights the need for more accurate and complex epidemiologic data along with appropriate HIV service programs.

The HIV epidemic affecting African-born immigrants and African-American requires sustained and multifaceted programming to address the different needs of the various segments that make up these populations. Programming that prevents new HIV infections should include an understanding of the complex factors which include socio-economic status, poverty, institutional and systemic racism, stigma, discrimination, and immigration status that prevent health service and treatment access.

Stronger alliances should be built with African-American and African-born immigrant communities in the U.S. to design culturally relevant interventions that promote HIV prevention, testing, and linkage to care. Given that the HIV epidemic is most pronounced among Black men who have sex with men and Black heterosexual women, education, prevention and treatment activities should be focused on these sub-populations.

Founded in 2002, the Global Fund is a partnership between governments, civil society, the private sector and people affected by AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. The Global Fund raises and invests nearly US$4 billion a year to support programs run by local experts in countries and communities most in need.

Each implementing country establishes a national committee, or Country Coordinating Mechanism, to submit requests for funding on behalf of the entire country, and to oversee implementation once the request has become a signed grant. Country Coordinating Mechanisms include representatives of every sector involved in the response to the diseases.

Nigerian migrants represent the highest migrant group in the U.S. Please click here for Nigeria’s Country Coordinating Mechanism.

-SOURCES

- http://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/how-many-slaves-landed-in-the-us/

- http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/sub-saharan-african-immigrants-united-states

- http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/03/5-facts-about-illegal-immigration-in-the-u-s/

- http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/03/5-facts-about-illegal-immigration-in-the-u-s/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3672242/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3263303/

- https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html

- http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/why-immigrants-lack-adequate-access-health-care-and-health-insurance

- http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/8/08-020808/en/

- https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_NHPC_Booklet.pdf

- http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/why-immigrants-lack-adequate-access-health-care-and-health-insurance

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4509742/pdf/nihms576300.pdf

- Millet G, Peterson J, Flores S et al. (2012a). Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 380: 341–48.

- https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2012/07/pdf/hiv_community_of_color.pdfhttps://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbt/reports/2012/07/27/11834/hivaids-inequality-structural-barriers-to-prevention-treatment-and-care-in-communities-of-color/

- UNAIDS and IOM, 2001

- http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en_1.pdf

- https://www.iom.int/world-migration

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3462414/

- http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0097596

- http://prostitution.procon.org/view.answers.php?questionID=000095

- https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_basics_ataglance_factsheet.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html

- https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/policies/care-continuum/

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/todaysepidemic-508.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/bmsm.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/sexworkers.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/idu.html

- http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1353&context=trotter_review

- https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/policies-issues/hiv-aids-care-continuum